As Newman put it, Boccaccio’s stories remind us of “our basic (and sometimes base) human qualities and the not-always pretty sides of our humanity that cannot be avoided even when allegories and artifice prevail.”Īnd, indeed, the first story introduces a character who reminds me of someone with orange hair who happens to lead a country that was once a beacon for freedom and intelligence. The stories delve into the full range of human behavior, from magnificent to despicable. (If you want to know more about The Decameron, you can watch her talk, here, and if you really get hooked, go to this Brown University site.) And the ones who remained had more power, and could demand higher wages. Although the plague killed as much as 60% of Europe’s population, she saw some upsides: It led to reforestation, because there weren’t enough peasants to farm the fields. In a set of slides, she showed pictures of cool things like the protective gear doctors wore in the 17th century, with masks that made them look like they had dressed up as birds. “His stories teem with a kind of diverse humanity,” Newman told us. She described the stories as allegories of the virtues, with the women representing qualities like prudence, justice, and fortitude, and the men representing anger, lust, and reason. Newman, professor of comparative literature at the University of California at Irvine, provided the historical context for the book, and after her talk, took questions from the other participants.

Last week, to gain better insight into the book, I joined 78 other people for a Facebook Live presentation sponsored by The National Humanities Center. It would certainly be more challenging than binge-watching TV shows I had missed and more satisfying than the Zoom cocktail parties that I’ve started avoiding, just as I did in real life, a term now poignant and expanded in meaning. Oddly, given my lust for fiction, I had never read The Decameron, probably because I didn’t major in English, where it no doubt would have been forced upon me. And it even prompted a key plot line in Richard Nelson’s latest play, What Do We Need to Talk About?, when one of the characters suggest they imitate the Florentines and tell timeless stories about the human condition to make them forget, perhaps for just an evening, the plague outside their doors.

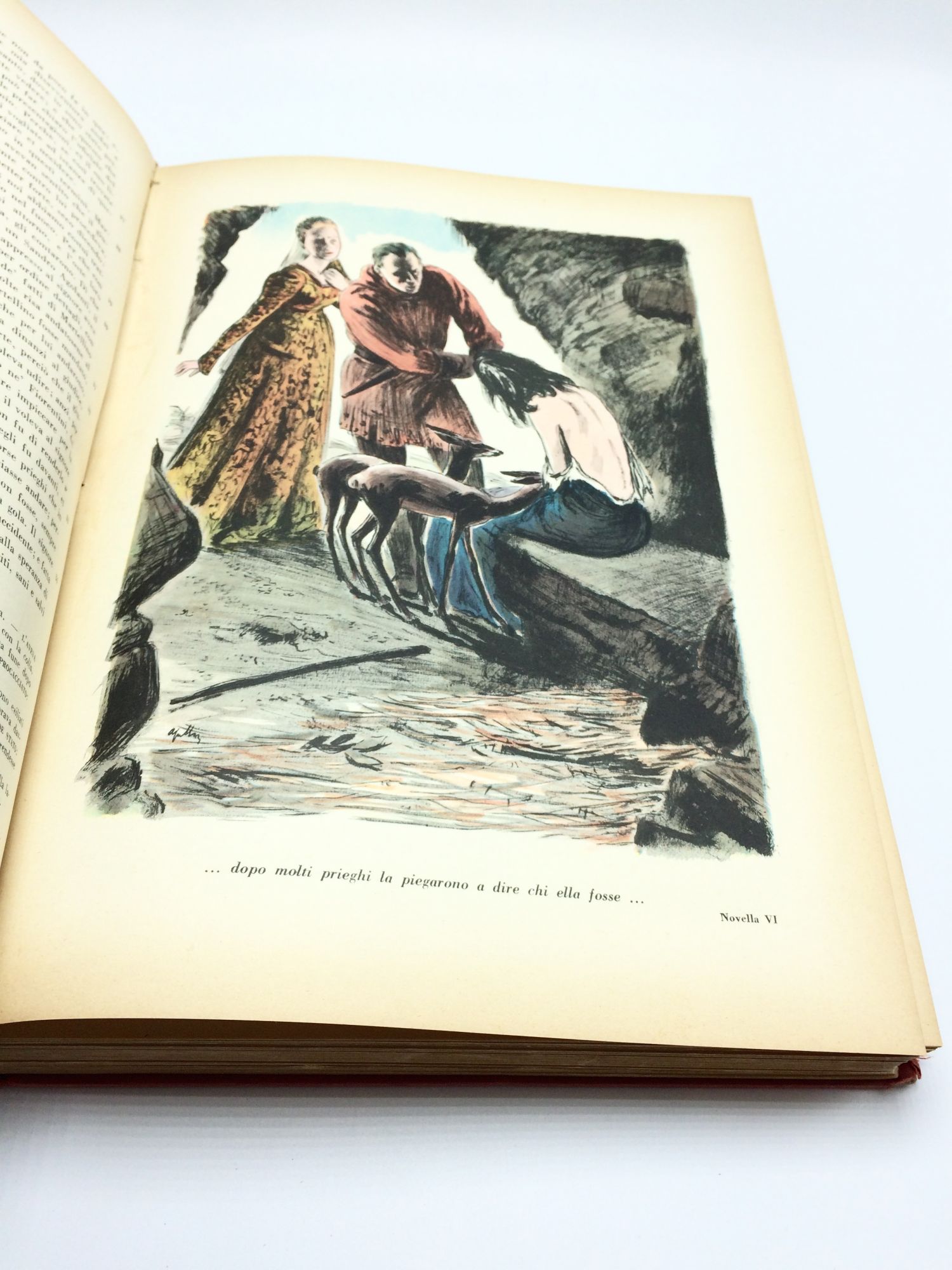

The classicist Daniel Mendelsohn tweets a new passage from it every day. The critic Eric Banks has been running a five-week, $150-per-person Zoom reading group in conjunction with McNally Jackson Books. Virtual books clubs are analyzing the 1353 masterpiece, consisting of a hundred stories told by three young men and seven women during their quarantine in a villa outside Florence. All of a sudden, everyone seems to be reading Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a novel published more than 600 years ago.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)